Jakob Feinig

Jakob Feinig

Binghamton University

The newly elected labor leader proposes that the Bank of England invest directly in infrastructure and housing. The Swiss are likely to decide about the abolition of bank-created money by popular vote. On the other side of the Atlantic, an economist and a hedge funds manager writing in Foreign Affairs suggest that the Fed should spend money directly instead of lending to banks to ensure that cash finds its way into citizens’ pockets. These proposals all have the potential to re-invigorate the politics of money.

In the United States, popular voices have since the 18th century demanded that money should be created by legislatures not banks. From Shays’ rebellion to 19th century Populism and William Jennings Bryan’s silver Democracy, the politics of money pitted creditors against debtors. From a long-term perspective, today’s absence of large-scale monetary reform movements in a context of hardship and debt crisis is an anomaly, not the norm. Even though unorthodox monetary medicines are peddled in venues such as Foreign Affairs, there is little prospect that they will be implemented. There is simply not enough popular knowledge and pressure that could translate into congressional action. Although banking regulation and inequality are debated, Americans hardly discuss the mechanism of money creation. We live in a period of monetary silence.

To begin understanding today’s monetary silence, we can turn to the Bonus March. In 1924, World War veterans received an “adjusted service certificate”, a government obligation cashable some two decades later, to compensate them for income lost during their service. When the Great Depression hit the country, millions of veterans, many of whom unemployed and in desperate need of cash, were in possession of a government debt. In 1932, the young representative Wright Patman, himself a World War I veteran, introduced legislation to finance an immediate payment of the bonus through the issue of government currency. He saw this not only as a payment the country owed the veterans, but also as a means of stimulating economic life and circumventing banks, which were accused of hoarding money. Congressional money would reach citizens who would spend it. Money was not simply a commodity in need of better regulation; it was a creature of the state and hence of democracy.

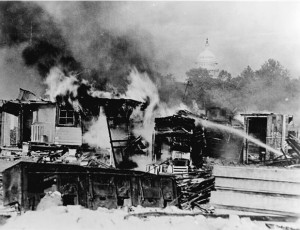

[Caption:] State violence in response to demands for state money. The army evicts veterans from Washington, D.C, 1932.

[Caption:] State violence in response to demands for state money. The army evicts veterans from Washington, D.C, 1932.

When Patman’s bill passed the House, tens of thousands of veterans converged onto Washington to pressure the Senate to adopt it. Like Patman, they considered that they acted in the interest of the country as a whole, and that congressional money creation was a way to address the crisis. The veterans self-organized in a military fashion, constructed shelters, and published a newspaper. When the Senate rejected early payment, they refused to leave, and Hoover ordered the army to remove them. In the process, the armed forces—using tanks, cavalry, and tear gas— killed two former soldiers. Hoover became even more unpopular after this move, which helped seal his fate in the election of 1932. After he won the election, FDR dealt with the veterans very differently.

Unlike the impoverished veterans of the Great Depression, the homeowners, students, and unemployed victimized by the post-2008 Great Recession have not made governmental money creation a central demand. While the veterans squatted in Washington to promote congressional money creation, occupy centered its attention on Wall Street, and on private institutions deemed corrupt. This was an effective choice in terms of garnering attention because of the immense symbolism of New York City’s financial district. But in a sense, it made occupy more a movement of protest than of change because, through the choice of this site, it did not challenge the centrality of private actors in matters of money creation. Today, although banking regulation and inequality have become a central part of the public debate thanks in part to occupy, we live in a situation in which money creation continues to be depoliticized. Despite the noise, we live in a period of monetary silence.

In the next post, I discuss the how FDR responded to veterans and their allies, drew a line between state spending and money creation, and helped set up a discursive and institutional structure that continues to shape public debate and political possibilities today.

Jakob Feinig is Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of Human Development at Binghamton University. He is a member of the editorial team of Policy Trajectories and can be reached at jfeinig@binghamton.edu.

One thought on “What the Great Depression’s Occupiers Teach us about Money”