When the new Congress meets in January, unified Republican control suggests that a shift toward the use of block grants is likely to take place. Under Paul Ryan, the House has proposed consolidating federal funding for both healthcare and social assistance into two block grants. Conservatives see this as fostering fiscally responsible innovation. Liberals see it as part of a nefarious plot to gut programs for the poor.

While American pundits and policymakers often discuss the historical shift to block grants during welfare reform, they rarely bring in comparative analysis to this debate. This is a mistake. Canada offers a fuller picture of the promises and pitfalls of block grants. In contrast to the U.S., where block grants make up a mere 1.5% of the federal budget, they account for about 25% of the federal budget in Canada – a country many hold up as a model for U.S. social policy. Moreover, the majority of these blocks grants are for the same functions Ryan has proposed – healthcare and social assistance. This leaves us with a puzzle: Why do block grants seem to work so well in Canada but not here?

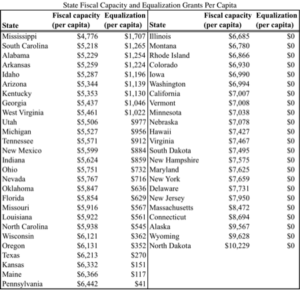

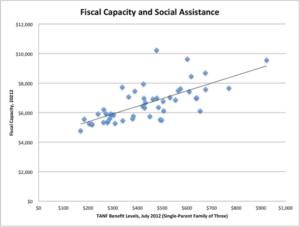

The key difference is that 25% of Canada’s block grants take the form equalization grants. These are federal transfers that only go to poorer provinces to bring their fiscal capacity up to the nationwide average. In the absence of equalization, even a poor state with the same tax rates as a rich state will bring in less revenue because of inequities in access to taxable resources (income, consumption, etc). Nobel Laureate James Buchanan argued equalization programs enable poor states to provide the same minimum level of public services without raising taxes higher than rich states. Without it – as is the case in the U.S. – we can expect to see poor states spend less on services, raise taxes, or both. This is exactly what we see when we look at the relationship between fiscal capacity and TANF benefits.

Sociologists often attribute meager benefit levels to conservative ideology or racial animosity, especially in the southern states, without even considering the fact that some states really cannot afford to spend more on the poor. The role of equalization in reducing interregional disparities in social assistance is striking. In 2013, a single mother receiving social assistance in the least generous American state (Mississippi) could expect to receive only 22% of the amount received by a single mother in the most generous state (New York). In contrast, a single mother in the least generous Canadian province (Nova Scotia) could expect to receive 65% of the amount received by a single mother in the most generous province (Ontario). This was not always the case. Prior to the introduction of equalization, Canadian provinces and American states had similar disparities in benefit levels.

So why doesn’t the U.S. have an equalization program like Canada? The answer is complex but it boils down to the refusal of rich (blue) states to transfer funds to poor (red) states for nothing in return. Although we don’t typically talk about it, Democrats spend much of their time defending policies that disproportionately benefit the wealthy states they represent. For example, California’s Maxine Waters recently defended the home mortgage interest deduction (HMID) while New York’s Charles Schumer has historically been the staunchest defender of the state and local tax (SALT) deduction. In 2014, these two tax expenditures cost the federal government $163 billion in foregone revenue with the majority of benefits going to rich taxpayers in rich states such as California, New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts. Meanwhile, equalization would have the most benefits for poor states such as Mississippi, South Carolina, and Alabama. Notice a pattern here?

By my estimates, a similar program of fiscal equalization for the U.S. would cost close to $121 billion. Eliminating the HMID and SALT deduction would provide more than enough revenue to fund such a program with one important political problem – it would entail a massive redistribution of resources from (rich) blue states to (poor) red states. As such, it is unlikely to gain the support of Democrats despite the impact it would have on reducing poverty through lower taxes and more robust social spending.

By my estimates, a similar program of fiscal equalization for the U.S. would cost close to $121 billion. Eliminating the HMID and SALT deduction would provide more than enough revenue to fund such a program with one important political problem – it would entail a massive redistribution of resources from (rich) blue states to (poor) red states. As such, it is unlikely to gain the support of Democrats despite the impact it would have on reducing poverty through lower taxes and more robust social spending.

This leaves us with a Catch-22. The use of block grants for social programs works best when accompanied by a program of fiscal equalization for poor states. Republicans have proposed expanding the use of block grants but have remained silent on the possibility of equalization grants, though it is likely they would be more open to it for self-interested reasons. On the other hand, Democrats continue to oppose block grants without understanding or appreciating their role in further entrenching regional inequalities based on fiscal capacity.

Complete Republican control on both the federal and state levels offers the chance to break us out of this vicious cycle. Congressional Republicans should use this opportunity to push their block grant agenda as long as they capitalize on Democratic weakness and push for conversion of unfair tax expenditures into an equalization program as well. It’s a politically smart strategy that would show Americans how Paul Ryan’s reform conservative agenda can successfully combine anti-poverty reforms with fiscal responsibility while offering a viable alternative to competing populist agendas within the GOP.

You are right that the deductions for mortgage interest and state and local taxes are regressive. One objection often raised to block grants is that it would allow states to cut taxes (mainly on the rich) and use the Federal money to make up for the shortfalls, so that social expenditures would not increase. The gap between rich and poor states would remain. Does Canada have measures to prevent national funds from going to provincial tax cuts and if so how do they do it?

Another concern is that health costs rise faster than most other expenses and Ryan’s plan is designed to limit increases in Medicaid to rates well below the general increase in health costs, leading to inevitable reductions in the health care given to the poor. This also is the concern with his plan to switch Medicare to a voucher for private health insurance. How does this work in Canada?

Interesting. I guess the other thing to think about is intent: in the US block grants have historically been accompanied by spending cuts, and they will be this time. One of the numbers I’ve heard thrown around about block granting Medicaid is that the block grants might only total 75% of pre-block granted federal transfers. I think that block granting in the United States would also produce a huge divergence between states (bigger even than we have now), whereas in Canada the ideological spectrum is, its fair to say, narrower. In Rhode Island, for example, the state would almost certainly use a Medicaid block grant to build a bunch of affordable housing, which they can’t do now. I’m not sure what Mississippi would do, but probably not that!

The CHT and CST must be spent on health and social assistance respective, with the provinces given lots of discretion in how exactly to spend it, but there are absolutely no strings attached to Canada’s equalization grant. Provinces can, and some have, use them for tax cuts.

I don’t see this as a problem for a few reasons. First, tax cuts are a good use of the funds. Let’s start with the example of Kansas, which has been in the news lately. Everyone has been calling it a radical experiment but the changes that have occurred in the last five or so years have had the effect of making Kansas’ tax structure look very similar to… Massachusetts. Of course, Kansas’ low fiscal capacity meant this led to a deficit there but not in Massachusetts. Equalization payments would have more than closed that deficit if they had been in place. A lot of folks don’t think interregional tax equity is important but I think it’s a really important goal to pursue so I’m fine with the Kansas tax cuts. More broadly, we know that limited fiscal capacity is correlated with more reliance on regressive taxation. This make sense because consumption taxes are “money machines” when it comes to raising revenue so its smart to rely on them if you have high demand for social spending combined with limited fiscal capacity. I’m willing to bet that sales taxes will be most likely to be reduced by states receiving equalization grants. Newman and O’Brien work suggest this is probably a good thing. Lastly, everyone who thinks it’ll all go to tax cuts forgets about the flypaper effect! The evidence suggests that some or much of it will go to more generous social spending rather than be returned to taxpayers. Republicans are no different in that they like to claim credit for providing benefits such as more education funding.

Regarding healthcare, we would have to ask why services for the poor haven’t decreased in Canada given that block grants have been in place for decades there. This suggests it’s really not inevitable as critics make it out to be and equalization is part of the reason. Everyone is pointing to Republican governors turning down “free” Medicaid expansions but neglect to mention the fact that states are on the hook for 10% of the new costs going forward after only three years. Where everyone sees cold-hearted Republicans, I look at the map of states that haven’t bought into the expansion and see fiscally responsible governors from states with limited fiscal capacity trying not to be overwhelming with new partially funded mandates.

To be honest, I think much of the concern that Republican controlled state governments won’t increase spending is based on a stereotype that they reason the spending isn’t higher already is because of anti-government ideology or racial animosity rather than the mundane reason of limited fiscal capacity.