Josh Pacewicz

Josh Pacewicz

Brown University

This election has brought much speculation about tension between Donald Trump and the Republican party, a closely watched issue with this week’s Republican convention in Cleveland. A person might reasonably wonder what is at stake in apparent presidential candidate-political party conflicts, and ultimately which side—the candidate or the party—stands to lose more from them.

If anything, this election season has shown that the question is a difficult to answer, because the boundary between American presidential campaigns and political parties are nothing if not blurry.

By this, I mean first to state the obvious: the political beliefs of Republican voters, everything they do to influence other voters, and their propensity to vote (“the party in the electorate,” to borrow a term from political theorist VO Key), is heavily colored by the presidential campaign itself. One could certainly make the case that Trump is articulating a new set of political cleavages that is more reminiscent of the European far-right than the traditional marriage of social conservatism and free market ideology that has historically defined the GOP, which could ultimately redefine how we understand the Republican Party. But at present, whether Trump really will redefine the GOP and the electoral consequences thereof is an open question—I’ll refrain from the predictions game.

What is also true, however, is that the Republican party as organization—that is, the political institutions, both formal and informal, that represent and act on behalf of the party—is similarly difficult to separate from the presidential campaign. Moreover and consequently, the Republican party has more to lose from this organizational standpoint from continued battles with Trump than vice versa. To clarify this, it is helpful to examine historical patterns of political spending in the United States, a rough proxy for the organizational capacity of various kinds of political actors:

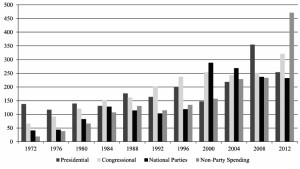

Election year political expenditures in millions

(1972-2010). Adjusted for inflation to 1972 dollars

Particularly before the 1980s, the numbers tell a clear story: historically, American political parties were national organizations in name only. This organizational incapacity of American parties is partially the historical legacy of the country’s rural beginnings. When tasked with mobilizing a population scattered over a wide, dangerous frontier, America’s first party builders balked, creating party organizations by stitching together loose alliances of local political machines, factions, and other parochial interests. The party establishment was little more than a few figureheads, with no institutional capacity to mobilize actors at even the state level, much less the grassroots. As late as the 1960s, for example, the DNC expended only $19.2 million and had fewer than 30 employees, a state of affairs that led the DNC president to complain that “the party” had the power to do only two things: hold the convention and establish rules for who could come. Historically, it was presidential campaigns that exerted any kind of sustained organizational effort, regularly expending more money than political parties and all congressional, state, and local campaigns combined. The organizational infrastructure of the party was revived every four years, as presidential campaigns wove together the party, mobilizing the grassroots base along a consistent message, bringing new activists into the fold, and so on.

Although this state of affairs has changed somewhat since the 1980s, it hasn’t changed very much. The big change since has been the expansion of non-party spending, particularly with the expansion of PACs and Super-Pacs, which have gone from a vehicle employed largely by labor unions to major fixtures of the political landscape. But while PACs can and do fill politics with much sound and fury via negative attack ads, they engage in virtually no organizational party building, in part because the peculiarities of the American legal system heavily regulate their ability to do so while defining negative campaign ads as constitutionally protected free speech. Formal parties have grown more organizationally robust, but haven’t constructed anything resembling a national bureaucracy. They still have virtually no connection—financial or otherwise—with local chapters. In fact, political parties have virtually no local presence of any kind. I spent nearly 3 years doing an ethnographic fieldwork project focused on electoral politics in Iowa, a key primary and general election swing state, and met exactly one paid representative of either political party. What parties do instead is hold the convention, transfer moneys to funds intended to help congressional and state politicians, and spend most of what remains—75% of it, based on one estimate—on negative television advertising. In effect, the parties are still a few figureheads in a room, except now these figureheads control what is basically a glorified advertising agency that specialized in negative campaign ads.

From this organizational standpoint, it is easy to see why the “Republican party,” if one may even call it that, needs Trump more than vice versa. Organizationally, the GOP consists of loosely coupled set of institutions that, due to lack of real organizational capacity or overarching structure, will likely do what they do regardless of who the GOP nominee is: launch attack ads against the Democrats. Lets not forget too who the Democratic nominee; the RNC has been prepping its anti-Clinton message for decades. On the flip side, the GOP needs Trump to run a campaign that energizes, revives and hopefully expands grassroots party institutions with fresh recruits. For the long term prospects of the party, he’s got to get traditional GOP volunteers excited and get new ones to show up too, volunteers who will stick around after this election to run phone banks, get out the drive operations, file paperwork, organize rallies, and do the countless other things that the party needs to elect congressional, state, and local politicians.

My suspicion is that Trump probably will– at least as well as McCain or Romney– who, in the case of my fieldwork at least, were operating with at a real deficit of enthusiasm among grassroots recruits than the Democrats. If anything, the Republican party’s activist base has already been growing more via anti-establishment Republicanism than via presidential campaigns since at least the mid-2000s—think Ron Paul’s insurgent campaign or the Tea Party. In my observations, longtime Republican activists initially decried these new arrivals as more reminiscent of 1960s revolutionaries than true Republicans, but quickly accepted them. This makes me think that the Trump campaign is more of an organizational alignment between the GOP grassroots and national party brand than a break with the status quo, but it is also possible that Trump has simply gone a bridge too far and will fracture the Republican party at the grassroots. In any case, those are the organizational stakes in Trump-GOP standoffs.

Josh Pacewicz is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Brown University. He is interested in contemporary American statecraft, particularly the interplay between federal policy and party politics, municipal finance, political advocacy and expertise, and more generally the democratic process.