Greggor Mattson

Greggor Mattson

Oberlin College

Is the European Project Falling Apart? screamed recent headlines as the European refugee crisis moved into chronic mode. Close European Union (EU) watchers can be forgiven for crisis fatigue, because the European project has been falling apart at least the disastrous failure of the 2005 European Constitution.

But before then, prostitution policy had already laid bare the gaps between state policies, supranational governance, and national cultures. Between 1998 and 2004, 11 parliaments of the then-15-country EU debated whether to regulate prostitution at the national level, something that had, until then, been de facto regulated by cities. These reforms struck in two different directions, however, exposing deep divisions within the European project, as demonstrated by the first four to adopt new national standards. The Netherlands and Germany legalized “sex work” from a labor perspective, imposing workplace safety standards to remedy exploitation in a dangerous job. Sweden and Finland, on the other hand, attempted to abolish prostitution from the public sphere to protect gender equality.

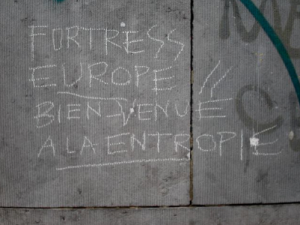

Fortress Europe: Welcome to Entropy. Author photo.

These differences were strikingly different among countries that, from an American perspective, seem strikingly similar: Northern European multiparty democracies with secular populations, strong welfare states, and strong human rights protections. Though the policy solutions were starkly different, they responded to similar realities and, paradoxically, had similar effects. The fall of the Iron Curtain unleashed waves of migration across Europe and prostitutes from non-EU countries dominated the sex markets of all four countries. Because these migrant prostitutes were not eligible for any benefits under these reforms, their fate was “repatriation” under abolitionism and “deportation” where sex work is legalized. Though prostitution reforms were justified according to local concerns, they came on the heels of EU plans to harmonize criminal justice and social welfare policy. The prostitute, a potent symbol of criminality and vulnerability, galvanized Member States to strengthen their national norms before unwelcome EU compromises could be forced upon them.

I argue that European conflicts over prostitution exposed implicit cultural understandings of welfare and citizenship. These taken-for-granted understandings framed the problem of prostitution in very different ways: as a crisis of gender equality in Sweden and Finland, but as a lack of worker support in Germany and the Netherlands. These correspond to well-documented differences between Nordic social-democratic welfare states and the so-called corporatist welfare states of the latter. Welfare state scholars are accustomed to thinking about three “worlds” of policy, but rarely articulate the relationships between financial entitlements and national culture.

Welfare states also institutionalize national commonsense about the good life, I argue, which is particularly potent regarding proper gender roles or sexual lives. More than bundles of social policies with financial effects, welfare states frame social problems and put national stamps on cultural politics and feminist social movements. Each nation’s prostitution debate was consistent with a general cultural repertoire embedded in welfare state policies and citizen expectations, forming the cultural tools by which citizens made sense of threats that demanded state solutions.

Prostitution reforms were methods by which governments apprehended women who were “loose” in the sense that they lacked formal or clear connections to state benefits, national labor markets, or international human rights protections. In my book, I show how anxieties about globalization created their own realities and political effects, even when the practical causes were the voluntary processes of European Unification and the different policies of erstwhile allies. Fears about globalization and the transfer of sovereignty to the EU created a context in which national parliaments asserted themselves by imposing national standards to protect vulnerable women. They thus strengthened states in the face of ostensibly global pressures, even while undermining their collective European project. Prostitution thus sabotaged the EU’s expansion to the “social dimension” of welfare policy, asylum rules, and criminal law. Anxiety over external threats to individual nations became articulated to disenchantment with the EU, sabotaging its goal to craft a coherent anti-trafficking strategy.

Prostitution policy remains a landmine that also has the potential to undermine the Common Market at the core of the Union. A group of experts concluded that the conflict over prostitution could justify trade sanctions by one Euro partner state against another:

The risk of compartmentalizing the internal market could justify the use of [an article to impose trade sanctions against a Member State] in such a situation . . . this example is not pure fantasy given the increasingly different approaches adopted by Member States as regards prostitution. (EU Network of Independent Experts in Fundamental Rights 2003, 14–15)

What the report didn’t note was that it was precisely which fundamental rights had precedence was the cause of the problem. Recognizing the labor rights of sex workers in the Netherlands and Germany conflicted sharply with the Nordic recognition of prostitution as a violation of women’s rights as human rights.

While many observers blamed the Greek debt crisis on too little political integration, prostitution policy had already exposed the lack of integration at the level of meanings: of vulnerability, citizenship, and welfare. These differences came to head during last year’s refugee crisis. If Europe couldn’t offer coordinated support for a handful of victims of human trafficking in flush times, it’s no surprise it is paralyzed in lean times by millions of less-sympathetic victims.

Greggor Mattson is Associate Professor of Sociology at Oberlin College where he teaches courses on sexuality, culture, cities, and law. He is the author of The Cultural Politics of European Prostitution Reform: Governing Loose Women (Palgrave 2016). He blogs at greggormattson.com and tweets @greggormattson.

One thought on “Prostitution Policy and the Unraveling of the European Union”