When and why do countries tax the rich? That’s the question at the center of Kenneth Scheve and David Stasavage’s aptly titled book, Taxing the Rich. The authors challenge a number of convention explanations for the rise and decline of taxes on the rich, including democracy, inequality, and the triumph of economic arguments. Instead, they argue that it can be explained by ideas about fairness: Countries tend to tax the rich when people believe that the state has privileged them in some way and taxes are seen as the best way to compensate for it. Specifically, they trace it to mass mobilization for WWI and WWII. In order to compensate for the burden placed on the masses by the military conscription of men, policymakers saw taxing the rich as the fair “conscription of wealth” for the same purpose.

In order to make their case, the authors rely primarily on a massive new dataset they assembled containing the statutory top marginal tax rates (MTR) for twenty countries between 1800 and 2013. Scheve, Stasavage, and Federica Genovese should be lauded for this much needed contribution to the literature on comparative tax policy. They buttress this with historical case studies of several countries where policymakers moved to tax the rich in the first half of the 20th century.

In order to make their case, the authors rely primarily on a massive new dataset they assembled containing the statutory top marginal tax rates (MTR) for twenty countries between 1800 and 2013. Scheve, Stasavage, and Federica Genovese should be lauded for this much needed contribution to the literature on comparative tax policy. They buttress this with historical case studies of several countries where policymakers moved to tax the rich in the first half of the 20th century.

Ironically, it is these historical case studies – not the quantitative analysis from the database – that provide the most convincing evidence for their argument. In chapter six, for example, they document the shift from “equal treatment” and “ability to pay” arguments in favor of income taxation in Britain before WWI to “compensatory” arguments after the outbreak of the war by coding parliamentary speeches from Hansard. This washed away my initial skepticism, helping me to see the importance of fairness as a justification in historical efforts to tax the rich.

Why is the database less convincing? The issue stems from their operationalization of “taxing the rich” as the top MTR. The authors readily admit the possible shortcomings of this particular measure, pointing out that some measure of top MTR relative to the median earnings would be superior but that the full schedule of income tax brackets for this entire period is simply unavailable. Using available data from six cases, they show that income taxes are clearly progressive in all countries that enact them but I’m less convinced their measure is useful for telling us if/how policymakers or the public taxed “the rich” as a distinct target population.

Rather than the top MTR, a better measure might be whether the government set a distinct tax rate via a separate bracket on the rich relative to everyone else. As Scheve and Stasavage point out, it would endlessly time-consuming to construct such a measure for all the years and countries they examine in the book. Clearly, we can’t fault them for not undertaking this additional work but it did make me curious about what difference this might make for our understanding of the politics of taxing the rich. Luckily, this data is available for more recent history.

The OECD has constructed such a measure by looking at the threshold at which the top MTR rate kicks as a multiple of the average wage in each country going back to 2000. Why is this important? Let’s compare the United States to Denmark. The top MTR in Denmark is almost 10 percentage points higher than in the U.S. (55.6% vs. 46.3%). Simply looking at this measure, one might conclude that the Danes have a stronger preference for taxing the rich than Americans. If we look at the threshold at which the top MTR kicks in though, we find that it 1.2x the average wage in Denmark versus 8.3x the average wage in the U.S. In other words, the top MTR in the U.S. specifically targets the 1% while the top MTR in Denmark applies to something like the top 40%. It’s hard to consider this a tax on the rich unless you consider earning the equivalent of $62,000 as rich.

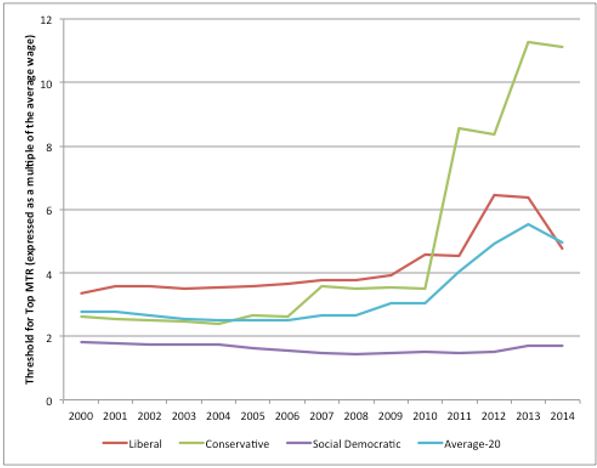

While clearly limited in scope, it offers a glimpse into the effect of renewed attention to the rich in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Whether we use the top MTR or the threshold for the top MTR paints two very different pictures. If we look at the average top MTR of Scheve and Stasavage’s twenty countries then it remains relatively stable at 47.4% pre-crisis (2000-2008) and 47.3% post-crisis (2009-2014). On the other hand, if we look at the threshold for the top MTR in the same twenty countries then we see a significant change with the top MTR kicking in at 2.7x the average pre-crisis and jumping to 4.5x post-crisis.

The picture becomes even more interesting if we break it down using Esping-Anderson’s typology of welfare regimes. Using four representative countries from liberal (US, UK, CA, AU), conservative (DE, FR, IT, AT), and social democratic (SW, DK, FI, NO) welfare regimes, we find a trend toward taxing the rich post-crisis in liberal and conservative – but not social democratic – welfare regimes.

This suggests that rising inequality and the financial crisis have indeed helped to precipitate a backlash against the 1% that has resulted in new efforts to tax the rich but that this has only occurred in particular welfare regimes. This is something that we would have been missed if we had only looked at top MTR as Scheve and Stasavage do in their book.

These findings leave us with new questions though. The trend for liberal welfare regimes are in line with Monica Prasad’s argument that these countries have “adversarial” political structures that encourage class conflict of this sort and also helps the absence of this trend in social democratic regimes. The fiscal sociology literature is hard pressed to explain the sharp rise in efforts to tax the rich among conservative welfare regimes though. Is this a new phenomenon or does it have historical precedent? It’s impossible to tell without data going back further than 2000. Let’s hope that Scheve, Stasavage, and Genovese further enrich the discussion by continuing to develop the Comparative Income Tax Database.