Daniel Laurison

Daniel Laurison

London School of Economics

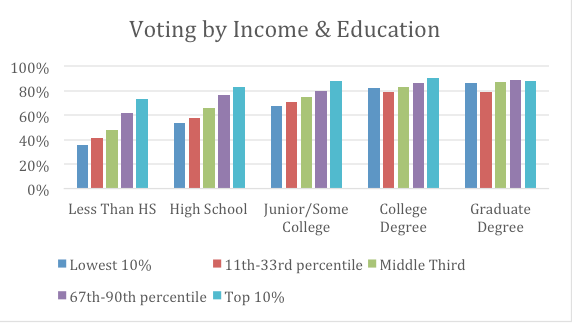

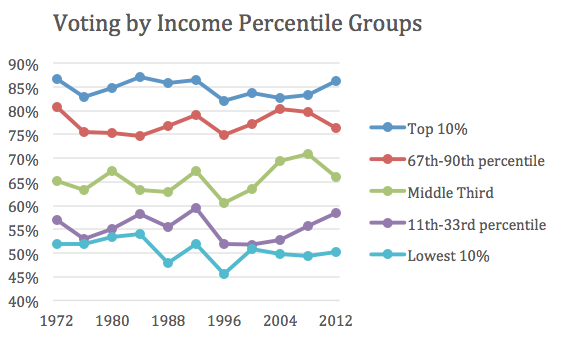

While there are no longer legal restrictions on voting for most[i] disadvantaged people in this country, there is nonetheless a steep class gradient in participation in American democracy: people who have less, vote less. As we watch the process of the 2016 Presidential election unfold, it is worth remembering that the voters whose poll responses are pored over by pundits, and who will elect the next President and congress of the United States, are better-off, on average, than the citizenry of the country as a whole.

The class gradient in political participation is not limited to voting. It also applies to talking about or following politics, giving time or money to campaigns, and most other forms of democratic engagement. Moreover, it holds within each of the major racial-ethnic groups in the United States, and for both women and men. Those with the least have the least voice, and those with more resources wield an outsize influence on our democracy, in substantial part just through participating more.

Source: Author’s analysis; General Social Survey data 1973-2014

Source: Author’s analysis; General Social Survey data 1973-2014

The question, then, is since (almost) everyone is equally formally entitled to participate in politics, why is there so much inequality in political participation? There are three main ways of answering this question among political scientists and sociologists. The first locates the sources of relatively low participation by the disadvantaged in their lack of the resources and attitudes required for the tasks of political participation (the definitive text is Verba Schlozman & Brady’s 1995 book Voice and Equality).

The next approach sees the interests of political elites and the barriers to participation as the main culprits. Work by those looking at participation comparatively and historically, such as Piven & Cloward, challenge individualist, resource-based explanations of classed non-participation in the United States. They argue that there is nothing inherent in having less income or education that leads to lower political participation. Instead, they cite the interests of elites and the structure of the party system as causes of class-stratified participation and engagement.

Both of these approaches focus on the logistical and administrative barriers to voting, but reforms meant to lower these barriers have actually tended to increase political inequality.

What I would call “relational” approaches offer a solution to this puzzle: they focus on people’s position in the social structure more generally, and their consequent relationship to government and political institutions; individual resources and institutional barriers are only part of the story of class inequality of political participation in the United States. There are socially-structured differences in how people see, relate to, and understand politics. Nina Eliasoph, for example, describes less-politically-involved people as believing that “the only people qualified to hold opinions are those who ‘have all the facts’” and therefore that “politics is not our responsibility. Politics is something that other people do, but not us” (page 134). As my research has shown, many poor and working class people feel less invited or entitled to participate in politics.

So where do these classed differences in relations to politics come from? The answer has a lot to do with how much connection people have to politics and government. There are a number of ways people with less income and education, in less professional jobs, are socially distant from politics: poorer people are less likely to be contacted by political parties and campaigns during elections, they are unlikely to see themselves in politics as the vast majority of politicians were in “white collar” occupations before running for office, and their social networks are less likely to include politicians, activists or high-propensity voters, both because their networks are smaller and because the people in their networks are also less well-off.

Class inequality in political participation has a number of important consequences. It means reports about likely voters’ opinions in polls, or actual voters’ choices, are skewed towards socio-economically advantaged people, not representative of the potential American electorate. Depictions of Trump voters as “working class” are one example of this: while Trump voters are more likely than other Republicans to say they are “working class” (as opposed to college-educated), these “working class” Trump supporters are almost certainly better off (on average) than the approximately 40% percent of eligible voters in the US who skip each election. (Figures in this post are from survey self-reports of voting; the percentage of non-voters in surveys are smaller than the actual number of non-voters because about 15% of people who say they voted in a given election didn’t.)

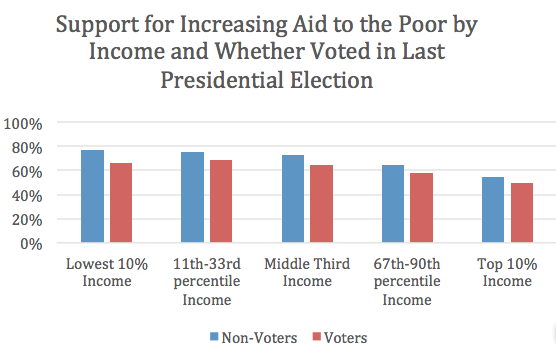

Similarly, reports about likely voters’ party preferences generally understate the degree of support that Democrats or redistributionist policies would receive if all those eligible to vote actually voted (and this does not include those ineligible to vote due to felony convictions or immigration status). Class inequality in political participation, then, tends to favor Republican candidates and inequality-promoting policies – outcomes that are generally bad for those who are already disadvantaged.

Source: Author’s analysis; General Social Survey data 2000-2014

But inequality in political participation is not an unsolvable problem. Mobilization or get-out-the-vote efforts can have a big impact on turnout; even so-called “low-propensity” voters generally ignored by campaigns can be encouraged to participate in politics, through conversations with their friends and neighbors and other grassroots outreach. Efforts to make meaningful connections between poor and working-class people and political campaigns and institutions can substantially reduce political inequality, by reminding disadvantaged citizens that they are, in fact, legitimate participants in the political process.

Daniel Laurison is a post-doctoral fellow in Sociology at the London School of Economics, and will be an assistant professor of Sociology at Swarthmore College starting in fall 2016. He studies political participation, campaigns, class and social mobility in both the US and the UK.

[i] The big exceptions are felon disenfranchisement laws and the recent upsurge of voter-ID laws, both of which disproportionately affect poor people and people of color.